PAPERBACK EDITION

$19.95 / £13.95

Available at

www.amazon.co.uk (out of stock)

Check here for alternatives

Hardback Edition available at

Use Back to return to pages on this web site that you have visited in this session, latest first.

Use Search to search this site for pages containing the word(s) or phrase that you enter.

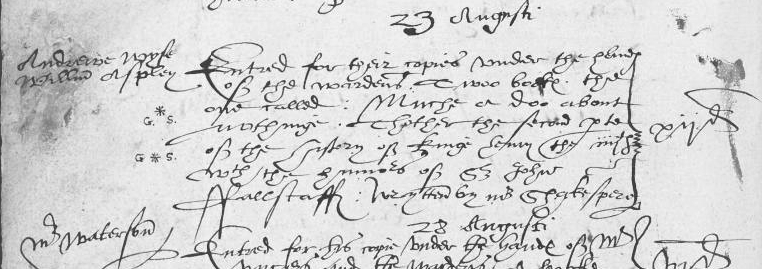

Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography

New Evidence of an Authorship Problem

All Contents Copyright © 2001-2023 Diana Price - All Rights Reserved (ver 1.6)

HOME

PAPERBACK EDITION

$19.95 / £13.95

Available at

www.amazon.co.uk (out of stock)

Check here for alternatives

Hardback Edition available at

Click Flip to see backcover

Click the lens to read the blurb and then click Back to return.

Update December 2025:

The London-based Shakespeare Authorship Trust’s Substack page distributes a newsletter a couple times a month. The December 6 issue linked to a segment of Lisa Wilson’s and Laura Matthias’s 2013 documentary, Last Will. & Testament. The segment was introduced by the producers (published free to the public, so below is an extract from their intro and the video link):

We are delighted to reshare this 12 minute video about the lack of a paper trail supporting the notion that the man from Stratford was a writer.

Inspired Unorthodoxy

When Laura Matthias and Lisa Wilson, SAT Trustee, documented Diana Price and her landmark publication, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography,

we became so inspired by her “Literary Paper Trails” investigation that we dedicated an entire sequence to it in the film “Last Will. & Testament.

The Declaration of Reasonable Doubt featured it, too, making Price’s comparative chart of Elizabethan/Jacobean writers one of the most compelling

arguments in Shakespearean authorship studies. Long may Diana’s work encourage balanced, unbiased enquiry.

Video clip is here.

Update June 2024:

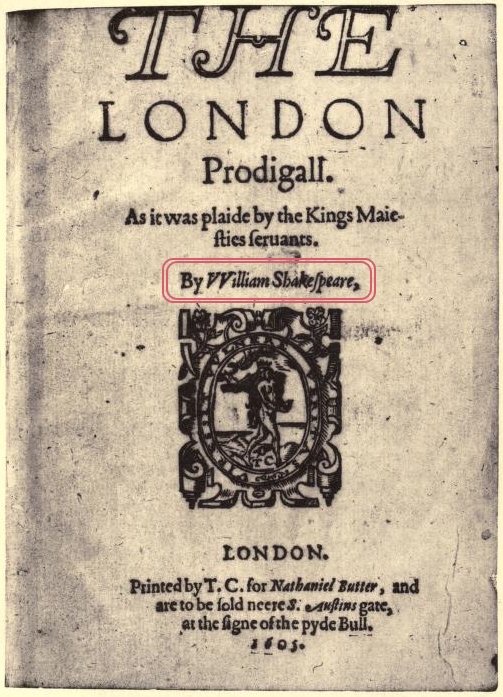

In his response to Henry Oliver’s “Shakespeare Wrote Shakespeare” at Oliver’s commonreader blog, Tom Woosnam responds: “A problem arises, however, when we find that not one of the 70+ documents attached to Shakspere’s life i.e. the primary source evidence of his family records and business dealings, gives even a hint that the Stratford man was an author of plays or poems. Even Sir Stanley Wells, the honorary president of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, acknowledges that fact. This is in stark contrast to 24 contemporaries of William Shakespeare’s (the author) from Ben Jonson to Christopher Marlowe for whom we do have documented evidence of literary authorship. See Diana Price’s brilliant book Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography for primary source evidence.

This makes William Shakespeare the only author since the invention of the printing press for whom all evidence of authorship is posthumous and, as it turns out, ambiguous. This is why people have questions.”

Update April 2024:

In an interview for the Shakespeare Authorship Trust in London,

Dr. William Leahy (Chairman of the Trust)

responded to two questions:

Q At what point did you begin to question the authorship of Shakespeare’s works?

A Diana Price's book, Shakespeare's Unorthodox Biography, was the turning point for me. At that time, it confirmed and deepened my own views that there was a problem

with the Shakespeare-of-Stratford-as-author narrative, but that evidence did not clearly identify an alternative.

Q What is the one book, talk, paper, movie, or television presentation you consistently suggest to those new to the authorship question?

A Diana Price’s book, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography.

UPDATE ca. spring 2024:

Alex McNeil's Shakespeare Authorship 101 YouTube video (promoting the case for Oxford) cites Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography starting around the 7½ minute mark.

Update January 2023:

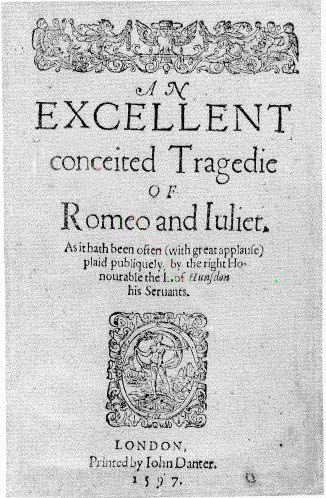

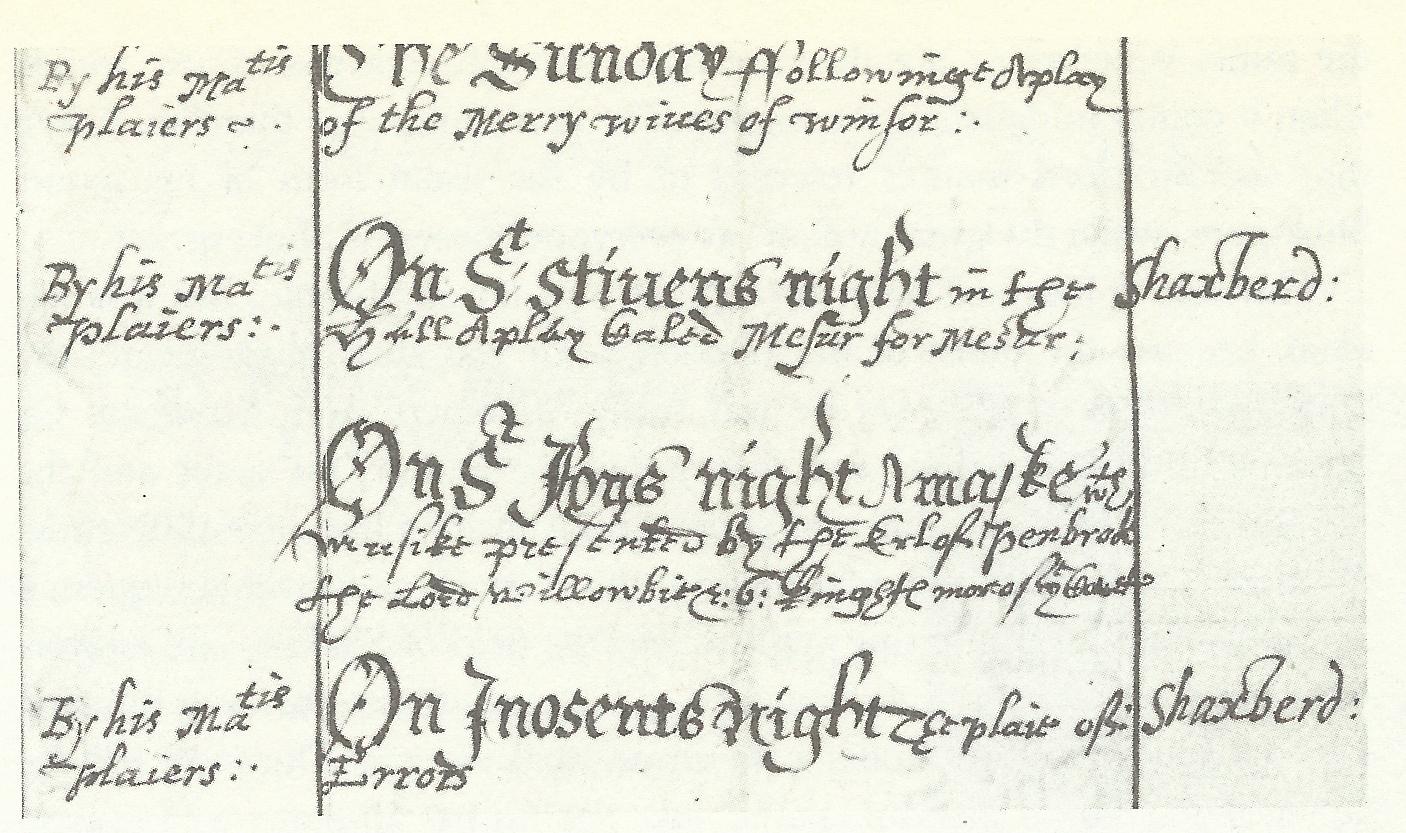

Chapter 10 (“The First Folio”) of Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography appears in its entirety and by permission in the January 2023 newsletter of the Shakespearean Authorship Trust. The edition celebrates the 400th anniversary of the publication of The First Folio.

Update August 2022:

Canadian actor Keir Cutler loaded up an improved (audio) version of my 2016 speech in Toronto on YouTube.

Update November 2021:

The paperback is no longer available at amazon.co.uk. You can still order from either Amazon in the US or email the author. If you buy from the author, the cost of the book plus s/h from the US will be approximately the same as was available at amazon.co.uk. For inquiries including payment and specific shipping costs based on prevailing rates, e-mail the author at .

Update September 2021:

The website has been redesigned to work better on mobile devices such as smart phones and tablets. It has also been moved to a secure platform.

Update March 30. 2021:

Al Hirschfield on Maybe Shakespeare Really Didn't Write the Plays" : "I am only posting this piece because the person in the first video, Diana Price, author of, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography;New Evidence of an Authorship Problem, was one of the most impressive "experts" in a completely mind blowing documentary I happened upon called, "Last Will and Testament" (free on Amazon Prime Video), and I could find very little else anywhere, on the internet or YouTube, about the Shakespeare authorship question" (includes the YouTube video link to Price's 2016 lecture in Toronto).

Update July 2019:

Diana Price responds to Oliver Kamm’s criticism in Quillette.

Update April 2019:

Joseph Hewes reviews Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography on YouTube.

Update February 2019:

From Sir Mark Rylance’s Foreword to Barry R. Clarke’s Francis Bacon’s Contribution to Shakespeare: A New Attribution Method (Routledge Studies in Shakespeare): “Read Diana Price’s excellent Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography and tell me I am wrong. I dare you!”

Update February 2019:

“Literary Paper Trails”: based on ch. 1 and the comparative chart in Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biographyy. In Critical Stages 18.

Update March 2018:

“My Shakspere: ‘A Conjectural Narrative’ Continued.” A chapter in My Shakespeare: The Authorship Controversy. Ed., William D. Leahy. Brighton, UK: Edward Everett Root Scholarly Publishers. Released February 28, 2018.

Price’s “Comparative Chart of Literary Paper Trails” appears in David Gowdey, “Secret Whispers: Searching for the Truth of Shakespeare” Amazon Digital Services LLC (August 2017). See also this customer review .

Update May 2016/September 2016:

Price’s 16-May-2016 email message to the British Library re: the Hand D Additions to Sir Thomas More. Day #: no change in the British Library’s claim that The Book of Sir Thomas More is Shakespeare’s only surviving literary manuscript. Update September 2016: the claim can now be found here.

Update January 2017:

An article cited in my Hand D paper in JEMS 5 is not at present accessible on the website listed; instead, please note the interim location: Matley Marcel B. (1992), Studies in Questioned Documents: Number Seven: Reliability Testing of Expert Handwriting Opinions. San Francisco, CA: Handwriting Services of California, <https://archive.org/details/ReliabilityTestingOfExpertHandwritingOpinions1992> accessed 2 January 2017.

Update May 2016:

YouTube: “Shakespeare Authorship Question Legitimized.” Diana Price discusses why the Shakespeare Authorship Question is a legitimate academic subject. This event commemorated the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare of Stratford’s death and took place on April 24, 2016, at the Berkeley Street Theatre in Toronto. Her remarks are introduced by Keir Cutler, PhD., who produced the video. Her remarks are also on YouTube as Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography By Diana Price. You can listen to Keir’s CBC interview where he discusses the authorship question and academia.

Update May 2016:

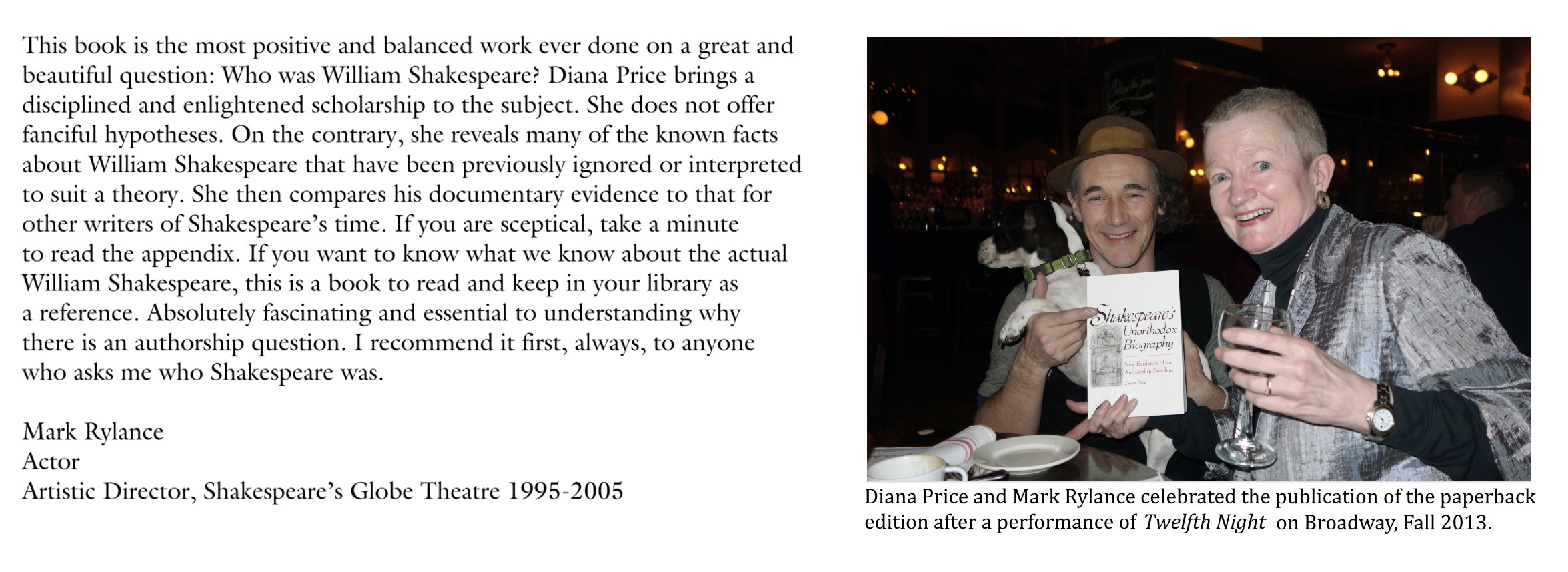

Mark Rylance and Sir Derek Jacobi discuss the authorship question in a YouTube video. At approximately 3:02 into the video, Mark holds up his copy of Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography and recommends it to viewers. See his blurb on the back cover of the paperback edition on the homepage of this website.

Update April 2016:

Diana Price’s article “William Shakespeare: Syrian Refugee Advocate?” is published on the American Thinker website. The article was prompted by the announcement, made by the British Library in March 2016, of a project to digitize early modern manuscripts, one of which is the collaborative play The Book of Sir Thomas More. According to the British Library’s website, the Hand D Additions constitute “Shakespeare’s only surviving literary manuscript.” Price’s article challenges that identification with reference to her Journal of Early Modern Studies research paper, published shortly before the British Library’s announcement. The announcement appeared in numerous media worldwide.

Update March 2016:

The website has been redesigned.

Update March 2016:

Price’s research paper on the Sir Thomas More manuscript, titled “Hand D and Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Literary Paper Trail” is now published in the Journal of Early Modern Studies, Jems 5 (University of Florence, 2016).

Update March/April 2016:

A special event, “Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: A Celebration,” commemorated the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, Sunday, April 24, at the Berkeley Street Theatre in Toronto. The event featured Keir Cutler speaking about his work, Shakespeare Crackpot and keynote remarks by Diana Price.

Update February 2015

Review in Notes and Queries.

Update January 2015

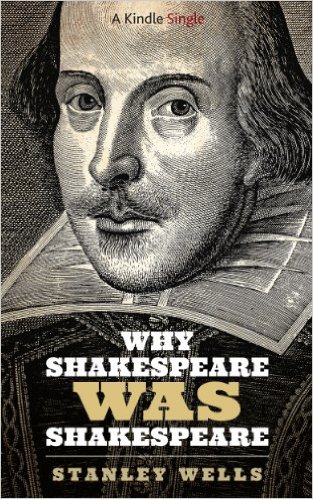

Prof. Stanley Wells concedes Price’s thesis again, this time in his comments published online in a Dec. 26, 2014 article in Newsweek (under the misleading title “The Campaign to Prove Shakespeare Didn’t Exist”):

Stanley Wells, in his Stratford office, sighs at having to repeat all the points he’s made over the years about Shakespeare’s identity. For

him, there is no mystery: “Yes, there are gaps in the records, as there are for most non-aristocratic people. We do, however,

have documentary records and there’s lots of posthumous evidence. There’s evidence in the First Folio, the memorial in the church here

in Stratford, the poem by William Basse referring to him, all of it stating that Shakespeare of Stratford was a poet,” he says.

…

What would settle this question for good? “I would love to find a contemporary document that said William Shakespeare was the dramatist of Stratford-upon-Avon written during his lifetime,” says Wells.

“There’s

lots and lots of unexamined legal records rotting away in the national archives; it is just possible something will one day turn up. That would shut the buggers up!” [emphasis added]

Price reviews Stanley Well’s Why Shakespeare WAS Shakespeare

Update May 2013

Stanley Wells reviews Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography An Unorthodox and Non-definitive Biography at Blogging Shakespeare. Now, his review can only be found using the Wayback Machine

Stanley Wells reviews Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography at Blogging Shakespeare. Now, his review can only be found using the Wayback Machine.

You can read Diana Price’s responses to these reviews posted by Pat Dooley in the Comments section.

Price reviews Shakespeare Beyond Doubt

Media coverage of the new paperback edition

Keir Cutler’s Shakespeare Crackpot video on YouTube (June 2014)

Quote from an Interview with Shakespeare Scholar and Editor Stanley Wells

[09/27/2013] Professor Wells discussed the Shakespeare authorship controversy, speaking and pronouncing Shakespeare, and editing Shakespeare’s texts.

“The best scholarly book by a non-Shakespearean is Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography, by

Diana Price.

I wrote several blogs recently trying

to refute her claims in that book. She knows a great deal; it’s just a great shame that her knowledge is put to such ignoble ends. The anti-Shakespeareans are

not necessarily ignorant people, some of them know a great deal. Nevertheless there’s something in their psyches that compels or persuades them to deny what

seem to me to be obvious truths.

…

This Brunel University in England, although they claim they’re not anti-Shakespearean, nevertheless has given

honorary degrees to Derek Jacobi, Mark Rylance and Vanessa Redgrave. They give honorary degrees to the three anti-Shakespeareans who are most prominent in the

public eye.

Some of them come out in favor of a particular candidate, and it’s interesting that Derek Jacobi was Marlowe until a few years ago until

he was paid for being in the film about the earl of Oxford. Mark [Rylance] is more circumspect. He’s more happy nowadays just to take the view that it wasn’t

Shakespeare. Diana Price is the same. Her book does not propound any specific candidate, it’s just saying that the evidence is against Shakespeare of Stratford.”

THE NEW YORK TIMES, SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2003

LETTERS

The Door’s Open

To the Editor:

The singular fact is that after 400 years, the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays remains an open question – no side has been able to close the sale. The greatest strength of the case for the man from Stratford is his incumbency, but no understanding of that case is complete without reference to Diana Price’s “Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography.”

Wayne Shore

San Antonio

Much Ado About Something A Documentary Film by Mike Rubbo (April 2002). “Diana Price has written one of the best books making the case against Shakespeare, Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography.. It was an inspiration in the final stages of making the film.”

Greensboro News & Record (by Trudy Atkins, 22 July 2001): “In this unique biography, Diana Price has researched every shred of evidence about the Stratford-born Shakspere, analyzing and interpreting literary allusions as well. What makes her biography unique is her examination of the same evidence for other writers of the Elizabethan and Jacobean periods. Her research seems to point to an overwhelming conclusion: that someone else wrote the works attributed to Shakespeare.”

Choice (by D. Traister, May 2001): “A deeply uninteresting exploration of a question that, for most scholars, is even more deeply unnecessary. Collections with a focus on Shakespeare and a fetishistic desire for “completeness” will acquire the book. So too might collections that specialize in extraordinary popular delusions and the madness of crowds.”

Academia: an Online Magazine and Resource for Academic Librarians (by Rob Norton, Jan. 2001, Vol. 1, No. 6), Profilers’ Pick: “Price argues compellingly that there is little evidence from life that the Stratfordian was the playwright William Shakespeare and that most of what we do know of Shakspere would make it impossible that he could have written plays and poetry clearly aristocratic in context, vocabulary, and sensibility. This book would be a good first stop for those seeking some introduction into this controversy and allow them to proceed intelligently to books written by those who have strong opinions as to the real identity of the Bard.”

Book News, Inc. (Portland, OR; booknews.com): “Price jumps into the eternal controversy with the unusual position of having no candidate to promote. Based on a systematic comparative analysis with other literary biographies, known biographical facts, and contemporary commentary, she concludes that William Shakespeare was the pen name of some anonymous aristocrat.”

Library Journal (15 November 2000): “Gives the Shakespeare doubters some very good ammunition…. Academic libraries should buy this book for the debate it will spark and the in-depth detective work it provides. Public libraries can safely pass.”

Northern Ohio Live magazine (by Michael L. Hays, April 2001): “The best unorthodox biography of Shakespeare in years. Well-researched and challenging … Price is the first to compare Shakespeare to a number of his contemporaries with respect to personal literary evidence. Her conclusion: He is unique in lacking any.”

The Elizabethan Review (by Warren Hope, 11/20/00): “Her book [is] unlike any book dealing with the Shakespeare authorship question that has appeared in years. … [It] tackles the question of who William Shakspere of Stratford actually was - a subject that has been too frequently ignored by Stratfordians and anti-Stratfordians alike… . Price works that field admirably and the harvest is abundant.” For the full review, click on Hope.

The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH, by Marianne Evett, 12/18/00): “Faulty logic and lack of knowledge of the broader social and theatrical milieu of the time undermine her argument. She uses a double standard for evidence.” For the author’s response, click on Response to Plain Dealer.

Peter Happé reviews the paperback in Notes & Queries (Feb. 2015) 142-145 [reviewed with Katherine Duncan-Jones’s Shakespeare: Upstart Crow to Sweet Swan 1592–1623 ]. Extract:

These two studies share much material about Shakespeare’s life and work but their

objectives and their methods are sharply contrasted…

Price writes a polemic which is engaged in promoting a view of Shakespeare’s life and

examining evidence about it, whether in its support or in rejection of such a view…

Because the material she reviews and the evidence she adduces and discusses are so wide

ranging the book is interesting and stimulating. It is apparent that many questions might

be asked about the details which have grown up around the life of Shakespeare… .

In spite of the polemical approach to some of these issues the book does point to and

leave open for further examination a considerable number of fascinating problems

generated in the canon and the life of Shakespeare…

The discussion of whether Hand D in Sir Thomas More is Shakespeare’s is intriguing in

view of the limited basis for comparison of attested samples of Shakespeare’s

handwriting which are so few. These are but a sample of the questions which Price raises

and one might hope that they will stimulate further enquiry.

Don Rubin reviews Shakespeare Beyond Doubt? (ed. Waugh and Shahan), which cites the literary paper trails comparative analysis from Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography (Critical Stages vol. 9, Feb 2014):

It is a woman, ironically, who lands the strongest shot of the battle, who sends the Stratford man

to the canvas with exactly that: “documentary evidence,” evidence that no one on the Wells’ team seems

able to stand up and refute. This solidest of evidentiary blows references authorship scholar Diana

Price and her own extraordinary book (Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography). It is Price who brings into

the battle some two dozen dramatists from the period. A core part of the Shahan book, she looks at each

writer in terms of education, correspondence concerning literary matters, proof of being paid to write,

relationships to wealthy patrons, existence of original manuscripts, documents touching on literary matters,

commendatory poems contributed or received during their lifetimes, documents where the alleged writer was

actually referred to as a writer, evidence of books owned or borrowed, and even notices at death of being

a writer. Such evidence, we find out, exists in some or even all of these categories for each of the writers

studied. For the Stratford man, however, not a single check in a single category. Stratford comes up blank.

The Wells team is silent here…

Stanley Wells reviews Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography An Unorthodox and Non-definitive Biography at BloggingShakespeare. Now, his review can only be found using the Wayback Machine

Diana Price responds to Stanley Wells’s review of

Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography

I am grateful to Professor Stanley Wells for following up on Ros Barber’s challenge to him and Paul Edmondson (eds., Shakespeare Beyond Doubt: Evidence, Argument, Controversy, Cambridge University Press, 2013, launched at the ‘Proving Shakespeare’ Webinar, Friday 26 April 2013). Barber criticized their collection of essays for failing to engage in the arguments presented in Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of an Authorship Problem ([SUB] Greenwood Press 2001; paperback 2013). As the first academic book published on the subject, it surely should have been addressed in essays relevant to Shakespeare’s biography. But better late than never.

In his review on Blogging Shakespeare (May 8, 2013), Prof. Wells takes issue with any number of details in my book, but he does not directly confront the single strongest argument I offer: the comparative analysis of documentary evidence supporting the biographies of Shakespeare and two dozen of his contemporaries. That analysis demonstrates that the literary activities of the two dozen other writers are documented in varying degrees. However, none of the evidence that survives for Shakespeare can support the statement that he was a writer by vocation. Now, his review can only be found using the Wayback Machine

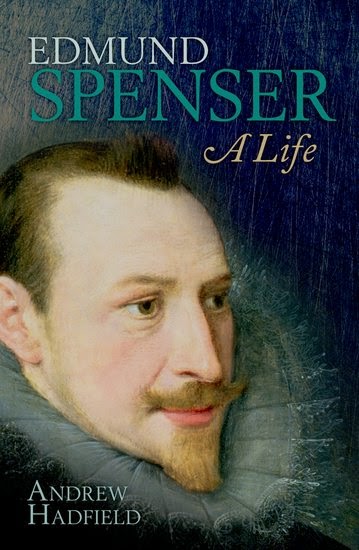

Wells is aware of this argument; in the Webinar, he alludes to Andrew Hadfield’s counter-argument, as first expressed in Hadfield’s 60-second video on the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust website. (The link is noe dead).

Question 16: Should we be concerned that there are gaps in [Shakespeare’s] historical record? … My favourite non-fact is that, although Thomas Nashe is, I think, the only English writer ever to have forced the authorities to close down the theatres and printing presses, making him something of a celebrity, we do not know when or how he died. Traces of Shakespeare, though scanty, do not require special explanation. Or, alternatively, we could imagine that a whole host of writers who emerged in the late sixteenth century, were imposters.

Hadfield repeats this explanation in his 2012 biography, Edmund Spenser: A Life (4). And it is true: we do not know how or when Nashe died. But we do know that Nashe left behind:

a handwritten verse in Latin, composed during his university days. His letter to William Cotton … refers to his frustrations “writing for the stage and for the press.” A 1593 letter by Carey reports that “Nashe hath dedicated a book unto you [Carey’s wife] … Will Cotton will disburse … your reward to him.” Carey also refers to Nashe’s imprisonment for “writing against the Londoners.” (SUB, 118)

Hadfield claims that, as with Nashe’s life, there are similar “frustrating gaps” in the lives of, for example, Thomas Lodge and John Webster. But Lodge refers to his books in personal correspondence and in a dedication, expresses gratitude to the earl of Derby’s father, who “incorporated me into your house.” There are payments to Webster for writing plays, and he exchanged personal commendatory verses with his friends Thomas Heywood and William Rowley. There is no comparable literary evidence for Shakespeare. Further contradicting his claim about the absence of literary evidence for Shakespeare and his contemporaries, Hadfield can cite solid literary evidence for Spenser. Such personal literary paper trails include his transcription of neo-Latin poetry in a book that he once owned, records of his education at Merchant Taylor’s and Pembroke Hall, and his handwritten inscription in a book he gave to Gabriel Harvey. There is no comparable evidence for Shakespeare. Yet Wells takes comfort that Hadfield’s explanations are true. From the Webinar Wells introduces

Theorising Shakespeare’s authorship by Andrew Hadfield… . That chapter really is incredibly helpful, I think, because it’s, its about helping us all to relax about that fact that we shouldn’t be worried about there being gaps in the records of people’s lives, or, that the kinds of records that we would most wish to see in someone’s life don’t in fact survive and aren’t there.

But the absence of personal literary paper trails for Elizabethan or Jacobean writers of any consequence is not a common phenomenon; rather, the absence of any literary paper trails for Shakespeare’s biography is a unique deficiency. In the Webinar, Wells expresses “no objection whatever to the validity of posthumous evidence.” Posthumous evidence can be useful, but it does not carry the same weight as contemporaneous evidence. Historians and critics alike make that distinction (see, e.g., here). Wells relies, as he must, on the posthumous testimony in the First Folio to prove that Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare. But even if he accepts the testimony in the First Folio at face value, no questions asked, no ambiguities acknowledged, he is still left with the embarrassing fact that Shakespeare is the only alleged writer of consequence from the time period for whom he must rely on posthumous evidence to make his case.

Wells has himself commented on the paucity of evidence. In his essay “Current Issues in Shakespeare’s Biography,” he admits that trying to write Shakespeare’s biography is like putting together “a jigsaw puzzle for which most of the pieces are missing” (5); he then cites Duncan-Jones who “in a possibly unguarded moment, said that Shakespeare biographies are 5% fact and 95% padding” (7). One difference, then, is that my work has no need for “guarded” moments, particularly as I re-evaluate that 5%.

Instead, of confronting the deficiency of literary evidence in the Shakespeare biography, Wells instead takes exception to particular statements and details in my book.

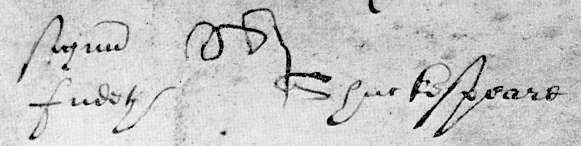

For example, he criticizes my references to Shakespeare’s illiterate household in Stratford, while at the same time I acknowledge that daughter Susanna could sign her name. And yes, she did, once. She made one “painfully formed signature, which was probably the most that she was capable of doing with the pen” (Maunde Thompson, 1:294), but she was unable to recognize her own husband’s handwriting. Her sister Judith signed with a mark. That evidence does not support literacy in the household; it points instead to functional illiteracy. In another criticism, Wells states that:

Price misleadingly says that ‘there are ‘no commendatory verses to Shakespeare’, ignoring those printed in the First Folio as well as the anonymous prose commendation in the 1609 edition of Troilus and Cressida and that by Thomas Walkley in the 1622 quarto of Othello.

In this criticism and elsewhere, Wells disregards the criteria used to distinguish between personal and impersonal evidence, explicit or ambiguous evidence, and so on. Such criteria are routinely used by historians, biographers, and critics (SUB, 309 and here). The prefatory material for Troilus and Othello necessitate no personal knowledge of the author and could have been written after having read or seen the play in question. (As pointed out above, the prefatory material in the First Folio is problematic, but the complexities require over a chapter in my book to analyze.)

“Price downplays William Basse’s elegy on Shakespeare … which circulated widely in manuscript – at least 34 copies are known – before and after it was published in 1633, and she fails to note that one of the copies is headed ‘bury’d at Stratford vpon Avon, his Town of Nativity’. Yes, and another version reads “On Mr. Wm. Shakespeare. He dyed in Aprill 1616.” There are various additional derivative titles.

I “downplay” this elegy for several reasons. Its authorship remains in question; it may have been written by John Donne, to whom it is attributed in Donne’s Poems of 1633. There is no evidence that either Basse or Donne knew Shakespeare. And yes, the elegy does exist in numerous manuscript copies; the one allegedly in Basse’s handwriting is tentatively dated 1626 and shows one blot and correction in an otherwise clean copy– suggesting that it might be a transcript.

The poem itself contains no evidence that the author was personally acquainted with Shakespeare. Whether by Donne or Basse, it is a posthumous and impersonal tribute, requiring familiarity with Shakespeare’s works, and, possibly, details on the funerary monument in Stratford. Wells and Taylor themselves cannot be certain which manuscript title (if any) represents the original (Textual, 163).

Wells concludes that “of course, she can produce not a single scrap of positive evidence to prove her claims; all she can do is systematically to deny the evidence that is there.” Questioning the evidentiary value of existing documentation is not the same thing as denying that documentation. It is true: I cannot prove that the man from Stratford was not the writer the title pages proclaim him to be, because one cannot prove a negative. However, I do demonstrate why there is an overwhelming probability that he did not write the works that have come down to us under his name. If he wrote the plays and poems, he would have left behind a few scraps of evidence to show that he did it, as did the two dozen other writers I investigated.

It is regrettable that Prof. Wells characterizes my book as an attempt to “destroy the Shakespearian case.” My book is an attempt to revisit the evidence and to reconstruct Shakespeare’s biography based on the evidence. Finally, I do not claim that my biography is “definitive.” But I think it is a step in the right direction.

Professors Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson reply ("Beyond Doubt For All Time") on Blogging Shakespeare 13 May 2013. Now, their reply can only be found using the Wayback Machine.

Diana Price replies to Professors Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson (14 May 2013)

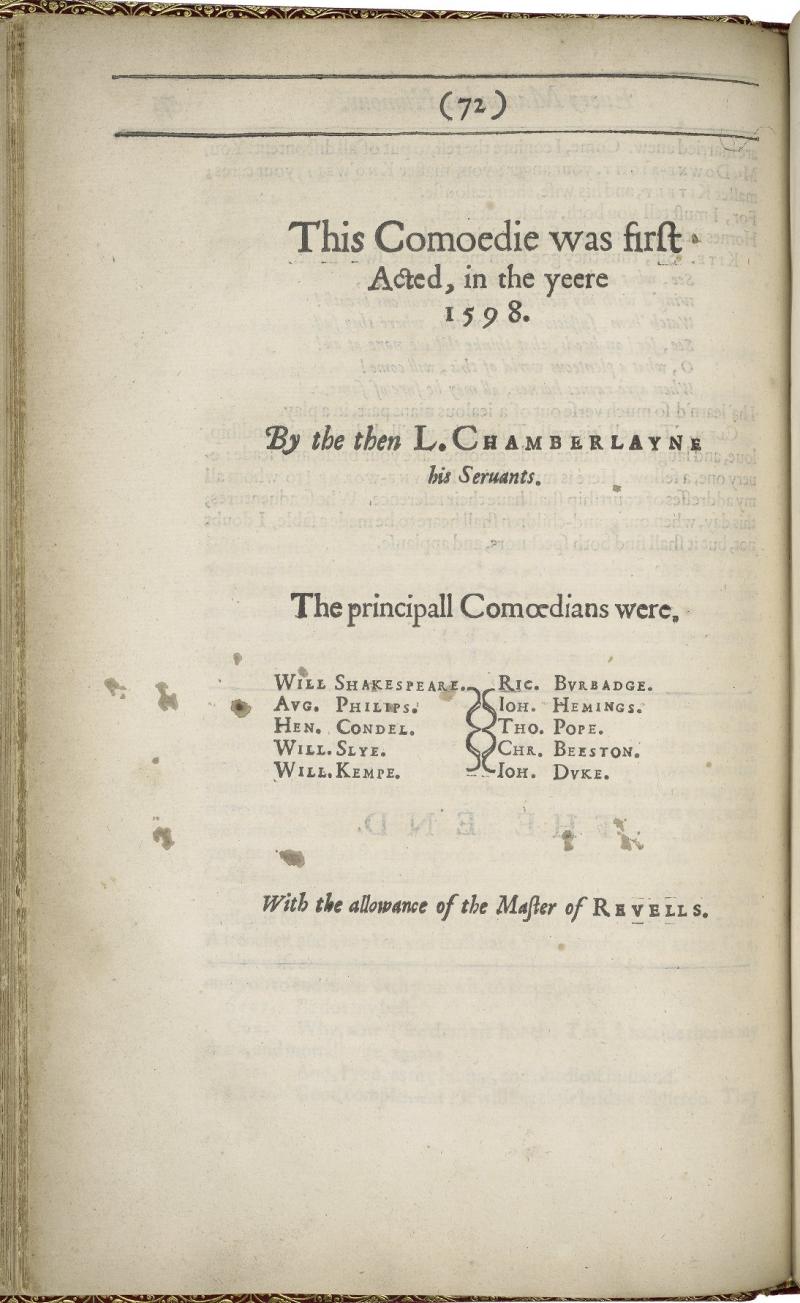

In their blog reply to my response to the Blogging Shakespeare 8 May 2013 review of Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography: New Evidence of An Authorship Problem (“Beyond Doubt For all Time,” 13 May 2013), Professors Stanley Wells and Paul Edmondson acknowledge that writers from the time period are documented to varying degrees, some more, some less. They imply that Shakespeare is in the “some less” category, so there are no grounds for suspicion. As Wells puts it, “The fact that some leave fuller records than others does not invalidate the records of those with a lower score.” Based on surviving evidence that supports his activities as a writer, Shakespeare not only rates a “lower score,” he rates a score of zero. At the time of his death, Shakespeare left behind over 70 documents, including some that tell us what he did professionally. Yet none of those 70+ documents support the statement that he was a writer. From a statistical standpoint, this is an untenable position, as I have argued elsewhere:

Even the most poorly documented writers, those with less than a dozen records in total, still left behind a couple of personal literary paper trails. Based on the average proportions, I would conservatively have expected perhaps a third of Shakespeare’s records, or about two dozen, to shed light on his professional activities. In fact, over half of them, forty-five to be precise, are personal professional paper trails, but they are all evidence of non-literary professions: those of actor, theatrical shareholder, financier, real estate investor, grain-trader, money-lender, and entrepreneur. It is the absence of contemporary personal literary paper trails that forces Shakespeare’s biographers to rely — to an unprecedented degree — on posthumous evidence. (“Evidence For A Literary Biography,” in Tennessee Law Review, 147)

While Wells and Edmondson acknowledge that Shakespeare is the only writer from the time period for whom one must rely on posthumous to make the case, Wells disputes my claim that Shakespeare left behind no evidence that he was a writer. The evidence he cites are “the Stratford monument and epitaphs, along with Dugdale’s identification of the monument as a memorial to ‘Shakespeare the poet’, Jonson’s elegy, and others” — all posthumous evidence. On the distinction between contemporaneous and posthumous evidence or testimony, Wells states:

I do not agree (whatever ‘historians and critics’ may say) that posthumous evidence ‘does not carry the same weight as contemporaneous evidence.’ If we took that to its logical extreme we should not believe that anyone had ever died.”

But historians and biographers routinely cite documentary evidence (burial registers, autopsy reports, death notices, etc.) to report that someone died. Wells may disagree with “whatever ‘historians and critics’ may say,” but I employ the criteria applied by those “historians and critics” who distinguish between contemporaneous and posthumous testimony (e.g., Richard D. Altick & John J. Fenstermaker, H. B. George, Robert D. Hume, Paul Murray Kendall, Harold Love, and Robert C. Williams).

Jonson’s eulogy and the rest of the First Folio testimony is posthumous by seven years, and it is the first in print to identify Shakespeare of Stratford as the dramatist. Posthumous or not, this testimony therefore demands close scrutiny. And I find in the First Folio front matter numerous misleading statements, ambiguities, and outright contradictions. I am not alone. For example, concerning the two introductory epistles, Gary Taylor expresses caution about taking the “ambiguous oracles of the First Folio” at face value (Wells et al., Textual Companion, 18). Cumulatively, the misleading, ambiguous, and contradictory statements render the First Folio testimony, including the attribution to Shakespeare of Stratford, vulnerable to question.

From my earlier response:

Wells concludes that “of course, she can produce not a single scrap of positive evidence to prove her claims; all she can do is systematically to deny the evidence that is there.” Questioning the evidentiary value of existing documentation is not the same thing as denying that documentation. It is true: I cannot prove that the man from Stratford was not the writer the title pages proclaim him to be, because one cannot prove a negative.

Prof. Wells now counters that:

Price defends her attitude by saying ‘one cannot prove a negative case.’ Why not? It is surely possible to prove that for example Queen Elizabeth 1 was not alive in 1604 or that Sir Philip Sidney did not write King Lear or that Professor Price does not believe that Shakespeare of Stratford wrote Shakespeare.

There is affirmative evidence that Queen Elizabeth died in 1603. Even allowing for uncertainties in traditional chronology, King Lear was written years after Sidney died in 1586. David Hackett Fischer elaborates on the logical fallacy of “proving” a negative when no affirmative evidence exists (Historians’ Fallacies, 1970, p. 62), and it is in that sense that I state that “one cannot prove a negative.” If there were explicit affirmative evidence that Shakespeare wrote for a living, there could be no authorship debate.

Please note: I am not a professor.

Bibliography

Centerwall, Brandon S. “Who Wrote William Basse’s ‘Elegy on Shakespeare’?: Rediscovering A Poem Lost From the Donne Canon” Shakespeare Survey 59 (2006).

Hackett, David Hackett. Historians’ Fallacies. New York: Harper & Row, 1970.

Hadfield, Andrew. Edmund Spenser: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

─────. “60 Minutes with Shakespeare” at https://60-minutes.bloggingshakespeare.com/conference/ (Dead link)

Price, Diana. “Evidence For A Literary Biography” in Tennessee Law Review 72 (fall 2004): 111-47. (accessible here)

‘Proving Shakespeare’ Webinar, Friday 26 April 2013, 6.30-7.30 BST. https://rosbarber.com/proving-shakespeare-webinar-transcript/ as of 9 May 2013.

Thompson, Edward Maunde. “Handwriting” In Shakespeare’s England: An Account of the Life and Manners of his Age, 1:284-310. 2 vols. 1916. Reprint, London: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Wells, Stanley. “An Unorthodox and Non-definitive Biography” on Blogging Shakespeare (May 8, 2013) Now, his review can only be found using the Wayback Machine

─────. “Current Issues in Shakespeare’s Biography” 5-21). In The Footsteps of William Shakespeare, ed. Christa Jansohn. Lit Verlag, Munster 2005.

Wells, Stanley, Gary Taylor with John Jowett and William Montgomery. William Shakespeare: A Textual Companion. 1997. Reprinted with corrections, New York: Norton, 1987.

University of Miami Law Review (Jan. 2003). “Could Shakespeare Think Like A Lawyer?: How Inheritance Law Issues in Hamlet May Shed Light on the Authorship Question” (by Thomas Regnier). “Diana Price’s recent Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography … meticulously demolishes the Stratfordian presumption.”

Radio National Perspective, Australian Broadcasting Corporation (by Prof. Patrick Buckridge, 25 March 2002). “At the core of Price’s book is a demonstration of just how exceptional Shakespeare’s case really is in comparison with his contemporaries in the theatre. … Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography was published by Greenwood Press, a respected American publisher, in their academic series, “Contributions in Drama and Theatre Studies.” This in itself is a remarkable breakthrough for a viewpoint that has hitherto been strictly quarantined to that part of the book market where wacky theories about the secrets of the Pyramids or the secret sex life of Billy the Kid are canvassed freely and with no impact at all on serious scholarship. It remains to be seen whether the book gets the serious attention it deserves.”

Studies in English Literature (by William B. Worthen, 2002): Price “follows the typical trajectory of anti-Stratfordian writing — [and] unfurls the usual wash of ’evidence’.”

Shakespeare Bulletin (by Prof. Daniel L. Wright, winter 2002). “Price’s text revisits the terrain of the Shakespeare authorship problem and sweeps away the detritus of conjecture. In doing so, she clarifies our understanding of why some of the problems related to Shakespeare are so vexing, contententious, and fascinating.”

History Today (August 2001). The cover story, “Who Wrote Shakespeare?” by Prof. William Rubinstein, examines the authorship controversy and suggests five books, including Shakespeare’s Unorthodox Biography for further reading.

Prof. Alan Nelson at his website (which is no longer available) (3/01): “Diana Price knows how to put a sentence together, but she does not know how to put an argument together without engaging in special pleading: that is, taking evidence that has an apparent signification, and arguing with all her might that it does not fit the special case of William Shakespeare for this or that special - and wholly arbitrary - reason.” For the author’s response, click on Nelson.

Prof. Alan Nelson replied to my rebuttal on his website at https://socrates.berkeley.edu/~ahnelson/ (which is no longer available): “Leonard Digges composed a handwritten inscription directly concerning William Shakespeare and directly touching on literary matters. … So close was Digges himself to Shakespeare that he called him not “Shakespeare," “William Shakespeare,” or “Mr. Shakespeare,” but - with singular affection and using his nick-name - “our Will Shakespeare". … “our” is simply the plural of “my", entirely appropriate in a literary discussion among three close friends, Will Baker, James Mabbe, and Leonard Digges.” For the author’s response, click on Response to Prof. Alan Nelson.

David Kathman, co-author with Terry Ross of The Shakespeare Authorship Website, contributed comments to “Shaksper,” the on-line orthodox discussion group, moderated by Prof. Hardy Cook: “Price’s book presents a superficial appearance of scholarship which may fool those not trained in the field, but in many ways this makes it more dangerous than the more obviously wacko anti-Stratfordian tomes which litter bookstore shelves.” Although Mr. Kathman explained that “Terry Ross and I have both been far too busy with more important matters to write up a comprehensive response to Price (doing exciting real scholarship is somehow much more fulfilling than refuting pseudo-scholarship),” he endorsed a lengthy review by Tom Veal (a much expanded version of his review on Amazon.com). Kathman directed “Shaksper" subscribers to Veal’s review, “which points out just some of its multitudinous faults.” Many of Veal’s criticisms are already addressed elsewhere on this website. For additional material on his criticism concerning the Sir Thomas More manuscript, click on More and page forward to pages 127-133.

One of Veal’s major criticisms is that I cite the Tudor “stigma of print” to explain why an arisotcratic playwright would need to conceal his identity. Veal cites The Shakespeare Authorship Page, which contends that the “stigma of print” is a myth. For the author’s response, click on Stigma of Print.

The Tudor stigma of print is a factor in my discussion of Shakespeare’s authorship. I discuss the matter in chapter 12 to explain why an aristocratic author would wish to conceal his or her identity, either in anonymity or behind a pen name. This essay responds to those critics who challenge the very existence of a Tudor “stigma of print” and further assert that my alleged failure to support my claims with adequate evidence is symptomatic of slipshod scholarship.

It is my perception that Tudor aristocrats did not wish to be perceived as interested in earning money for professional work. That was the province of the commercial class, and earning money by writing was viewed as professional activity. The stigma of print therefore affected what the aristocrat wrote and whether it was published.

Tudor England was still largely a manuscript culture, and “the recognized medium of communication was the manuscript, either in the autograph of the author, or in the transcription of a friend” (Marotti, Donne, 4). The transmission of manuscript into print was influenced by a socially-imposed stigma of print which affected some genres much more than others. It had less effect, for example, on the publication of pious or didactic works, learned translations, historical treatises, or the like. Such educational or devotional tracts had no taint of commercialism.

More to the point here, any nobleman good enough to write professionally could not be seen to be doing so. I argue that in the social caste system of Tudor England, aristocrats chose not to publish certain genres considered commercial, such as satires, broadsides, or plays written for the public stage, or frivolous genres, such as poetry. Some of these distinctions are covered in chapter 12, where I cite the evidence concerning the dramatic writing of the earls of Derby and Oxford. This essay is to augment the evidence in that chapter and respond to recent criticism.

David Kathman and Terry Ross, authors of The Shakespeare Authorship Home Page, propose that the stigma of print is an anti-Stratfordian fantasy. As far as I can tell, their challenge relies entirely upon a 1980 article by Stephen May, Tudor Aristocrats and the Mythical “Stigma of Print," which is reproduced on the website with accompanying commentary:

As May demonstrates, “Tudor aristocrats published regularly.” The “stigma of print” is a myth. May does concede that there was for a time a “stigma of verse” among the early Tudor aristocrats, “but even this inhibition dissolved during the reign of Elizabeth until anyone, of whatever exalted standing in society, might issue a sonnet or play without fear of losing status.” This essay first appeared in Renaissance Papers. (Kathman & Ross)

More recently, in a review on Amazon and on his own website, Tom Veal has attempted to provide some more meat on the bone, although his reliance on The Shakespeare Authorship Home Page is evident. In his dismissal of my scholarship, David Kathman recommended Veal’s criticism to the orthodox discussion group, “Shaksper” (Feb. 8, 2002):

I hope you’ll allow me to direct SHAKSPER

readers to a lengthy review of Ms. Price’s book which points out

just some of its multitudinous faults:

https://stromata.tripod.com/id115.htm

Terry Ross and I have both been far too busy

with more important matters to write up a comprehensive response to

Price (doing exciting real scholarship is somehow much more

fulfilling than refuting pseudo-scholarship), but last year Terry

wrote up some rather lengthy responses to specific points and posted

them at humanities.lit.authors.shakespeare. [links via Google; see

Bibliography below]

Price’s book presents a superficial appearance of scholarship which may fool

those not trained in the field, but in many ways this makes it more

dangerous than the more obviously wacko anti-Stratfordian tomes

which litter bookstore shelves. See the above review and posts for a

small fraction of the problems with it.

Following Kathman’s endorsement of Veal’s review, I decided to begin to respond to major points of criticism, and the allegedly “mythical” stigma of print seemed a good place to start.

I disagree with Prof. May’s conclusion for several reasons. One, the very evidence that he cites to demonstrate why the “myth” of the stigma of print was first postulated is, in my view, evidence of a genuine social dynamic. Among that evidence is The Arte of English Poesie (1589):

Now also of such

among the Nobilities or gentrie as to be very well seene in many

laudable sciences, and especially in making or poesie, it is so come

to passe that they have no courage to write, & , if they have,

yet are loath to be a knowen of their skill., So as I know very many

notable Gentlemen in the Court that have written commendably, and

suppressed it agayne, or els suffred it to be publisht without their

owne names to it: as if it were a discredit for a Gentleman to seeme

learned and to show him selfe amorous of any good Art.

(Elizabethan Critical Essays :2:22).

And in her Maiesties

time that now is are sprong up an other crew of Courtly makers,

Noble men and Gentlemen of her Maiesties owne servaunts, who have

written excellently well as it would appeare if their doings could

be found out and made publicke with the rest; of which number is

first that noble Gentleman Edward Earle of Oxford.

Thomas Lord of Bukhurst, when he was young, Henry Lord

Paget, Sir Philip Sydney, Sir Walter Rawleigh, Master

Edward Dyar, Maister Fulke Grevell, Gascon,

Britton, Turberuille and a great many other learned

Gentlemen, whose names I do not omit for envie, but to avoyde

tediousneffe, and who have deserved no little commendation.

(Elizabethan Critical Essays :2:63-64).

The stigma of print, as

discussed here, especially applies to verse. It is worth noting that

the author of The Arte of English Poesie chose to remain

anonymous himself.

May concludes that

there was a “stigma of verse” but no general “stigma of print.” I would

infer, then, that the stigma of print, such as it was, was confined

to the genre of poetry. By extension, other genres,

regardless of worth or respectability (including plays, whether

verse or prose), must have remained unaffected. But that scenario

does not, in my view, sufficiently distinguish between either social

class or genre, nor does it explain the absence of creative

works published by the nobility.

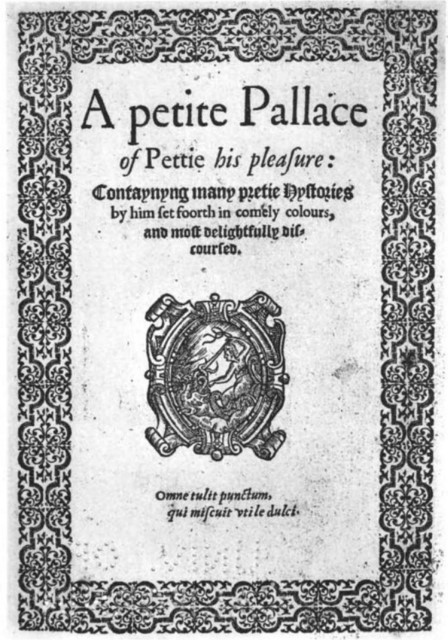

George Pettie offers

testimony to a general reluctance of the Tudor gentleman to betray

his learning by writing and publishing anything, even serious

matter, and his statements support the existence of a stigma of

print. Pettie adopts some typical poses to explain his own

appearance in print:

A Petite Palace is prefaced by three letters that fictitiously describe

how it came to press against the will of its author. In the first,

“To the Gentle Gentlewoman Readers,” one “R. B.” recounts his role

in the “faithless enterprise,” claiming that he named the work after

Painter’s Palace of Pleasure. Having heard Pettie give the

stories “in a manner ex tempore ” on many “private occasions"

and having learned that he had then written them down, R. B.

apparently begged the manuscript from his friend, promising to keep

it for private use. But fervent admiration for the opposite sex

drove R. B. to “transgress the bounds of faithful friendship” and

publish the stories for the “common profit and pleasure” of readers

“whom by my will I would have only gentlewomen.

In the second

prefatory letter -- supposed to have accompanied the manuscript when

Pettie confided it to his treacherous friend -- Pettie asks R. B. to

keep the manuscript secret because “divers discourses touch nearly

divers of my near friends.” The third letter is from the printer,

who claims to know neither Pettie nor R. B. but to have been given

the manuscript by a third party. Alarmed by the “too wanton” nature

of the work, the printer then “gelded” it of “such matters as may

seem offensive.” Authorial disavowal of an intention to publish was

not uncommon in the late sixteenth century; such a stance represents

an attempt to circumvent the class derogation attached to print. But

Pettie’s second work, The Civil Conversation, maintains the

fiction that his first was published without his permission.”

(Juliet Fleming,

Dictionary of Literary Biography 136:

Sixteenth-Century British Nondramatic Writers

. Ed. David A.

Richardson. The Gale Group, 1994.)

In Pettie’s preface to his translation of The Civile Conversation, we read further:

“a trifling woorke of mine [Pettie Palace ] (which by reason of the lightnesse of it, or at the least of the keeper of it, flewe abroade before I knewe of it). … I thought it stood mee upon, to purchase to my selfe some better fame by some better worke, and to countervayle my former Vanitie, with some formal gravitie. …for the men which wyll assayle me, are in deede rather to be counted friendly foes, then deadly enemies, as those who wyll neyther mislyke with me, nor with the matter which I shall present unto them, but tendryng, as it were, my credite, thynke it convenient that such as I am (whose profession should chiefly be armes) should eyther spende the tyme writing Bookes, or publyshe them being written. Those which mislyke studie or learning in Gentlemen, are some fresh water Souldiers, who thynke that in warre it is the body which only must beare the brunt of all, now knowyng that the body is ruled by the minde, and that in all doubtfull and daungerour matters: but having shewed els where how necessarie learning is for Souldiers, I ad only, that if we in England shall frame our selves only for warre, yf we be not very well Oyled, we shall hardly keepe our selves from rusting, with such long continuance of peace. … Those which myslike that a Gentleman should publish the fruites of his learning, are some curious Gentlemen, who thynke it most commendable in a Gentleman, to cloake his arte and skill in every thing, and to seeme to doo all things of his owne mother witte as it were: … they wyll at the seconde woorde make protestation that they are no Schollers: whereas notwithstanding they have spent all theyr time in studie. Why Gentlemen is it a shame to shewe to be that, which it is a shame not to be? In divers thynges, nothynge to good as Learning.

Pettie defends the idea of publishing serious work, although he explains that he is publishing Civile Conversations to make up for the triviality of Pettie Palace. There is of course no reason for Pettie to recite such an exercise if there was no stigma attached to publishing in the first place.

Pettie’s words also suggest perceived distinctions between serious and not-so-serious genres. May cites numerous publications to demonstrate the non-stigma of print, but most of these works could not be characterized either as frivolous or as commercial. Some even include apologies for poetry (such as Sir John Harington, who writes in the preface to his translation of Ariosto: “Some grave men misliked that I should spend so much good time on such a trifling worke as they deemed a Poeme to be” ( Elizabethan Critical Essays, 2:219). According to McClure, Harington “despised the professional man of letters. … In an age when the writing of verse was a gentleman’s pastime, he employed his talents for the entertainment of himself and his friends": “I near desearvd that gloriows name of Poet; / No Maker I … / Let others Muses fayn; / Myne never sought to set to sale her writing” (Epigrams, 34). (Note also that when his translation was first published, Harington had no title.)

Creative poems were considered literary trifles or frivolous toys, which accounts for the reluctance to be seen writing poetry as a full-time occupation. In contrast translations and closet dramas were educational and suitable for study. But plays written for the public stage were worse than frivolous. They were commercial, and public theater itself was often viewed as downright disreputable. Nevertheless, if there was no stigma of print, or if any authorial shyness was just an affectation, then we should expect to identify various members of the nobility who published their poems and plays, with or without apology.

On the other hand, if there was a stigma of print, we should expect to find some sort of correlation between social rank, genre, and publishing, i.e., the higher the social rank of the author, the more reluctance to publish; and the more frivolous or commercial the genre, the more reluctant the author. According to Arthur Marotti, “literary communication was socially positioned and socially mediated: styles and genres were arranged in hierarchies homologous with those of rank, class, and prestige” (Marotti, “Patronage,” 1). One would therefore expect to see the effect of the stigma of print on something of a sliding scale, having even an exponential effect on publishing as we climb the social ladder. At the top end, we should expect find very few, if any, of the nobility choosing to publish anything. Of those few books that might be published with authorization, the genre should be serious, educational, political, or devotional. Then, as we descend the social ladder, we should expect less serious genres to appear, with or without authorization, or with apology. And when at last we find self-proclaimed poets or dramatists (or satirists or fiction writers) freely and openly publishing their creative work, we should be looking at the lowest rungs of the gentry and the commoners, the would-be’s, the aspiring amateurs, the professionals affecting the conduct of the gentleman-amateur. And that is exactly what we find.

Many members on the top rungs of the Tudor aristocracy had outstanding reputations as poets. But none of them published their creative work. The earl of Surrey’s attributed poems were published in miscellanies after his death. So were Thomas, [Baron] Lord Vaux’s. The earl of Oxford published nothing during his lifetime. Further down the social ladder were Sir Philip Sidney, Sir Walter Raleigh, Sir Edward Dyer, and Sir Fulke Greville, all of whom also earned reputations as writers. None of them published their work, either. Like those of their social betters, the relatively few poems that appeared in print turned up in miscellanies. So here we have just what we should expect if there were a stigma of print. All these poets established literary reputations either on works transmitted orally, circulated in manuscript, or in miscellanies published by someone with access to those circulating manuscripts. It is not until one descends to the aspiring gentlemen, the would-be’s, those seeking preferment, and of course the newly emerging class of professionals (e.g., Greene and Nashe) that one finds unrestrained (and even then often apologetic) efforts to publish.

May acknowledges that “To all appearances the code [of the stigma] was upheld by the next generation of courtier poets, insofar as Sidney, Dyer, Ralegh, and the earl of Essex, among the more prominent Elizabethan courtiers, likewise made no provision to publish their works.” But it is that appearance of conformity to the social code -- that very failure to publish -- by the highest-ranking poets of reputation in Elizabethan and Stuart England that demonstrates the stigma of print. The stigma of print is manifested first and foremost with the nobility, and is gradually diluted as we descend the social ladder. The members of the nobility in Tudor and early Stuart England are relatively few in number, and their ventures into publishing almost nil.

Most of the plays written by aristocrats were closet dramas, not intended to be performed, and more properly categorized as learned translations or political treatises. Even so, nearly all the closet dramas that were published were either unauthorized or were printed posthumously. The Countess of Pembroke was the highest ranking aristocrat who published a (possibly authorized) play, and it was closet drama. The earl of Derby wrote plays for common players, but none survive, at least not under his own name. If other aristocrats wrote plays for the public stage, history does not record what those plays were, and none were published with attribution. William Alexander was a Scot and had no title when he published his four closet dramas. Greville recorded his reluctance to see any of his plays published, even posthumously.

Many of the works May cites to deny a stigma of print are political, pious, or didactic works and translations, which, as we move down the social ladder, were published with less restraint and, even so, often with apology by the upper classes. And those aristocrats (e.g., Oxford or Raleigh) who contributed prefatory material to other men’s work were appearing in the role of patron, which did not constitute a social breach.

May concludes that “the substantial number of upper-class authors who published during the sixteenth century effectively discredits any notion of a generally accepted code which forbade publication, since noblemen and knights, courtiers and royalty, trafficked with the press in ever-increasing numbers.” But this is contradicted not only by Pettie’s testimony but also by the publishing record. No member of the Tudor nobility published poetry, plays, satires, or the like. May’s examples include authors from the Caroline period (e.g., the Cavendishes or Fanshawe), too late to be relevant to the period. He also lumps the top rungs of the aristocracy in with the middle and lower gentry and even those yet to receive their title. The only verse pamphlet by Sir John Beaumont was published when he was less than 20 years old, and he did not become a “Sir” until just before he died. Thomas Sackville had no title when Gorboduc was published.

Finally, we have the testimony of dozens of untitled writers who aspired to the code of the gentlemen-amateurs, who wished to wash the money and printer’s ink off their hands. Ca. 1603, Samuel Daniel wrote:

About a year since, upon the great reproach given to the Professors of Rime and the use thereof, I wrote a private letter, as a defense of mine owne undertakings in that kinde, to a learned Gentleman, a great friend of mine, then in Court. Which I did rather to confirm my selfe in mine owne courses, and to hold him from being wonne from us, then with any desire to publish the same to the world" (A Defense of Rhyme, in Elizabethan Critical Essays :2:357).

Here we see Daniel posturing to emulate the code of the aristocracy. Like Daniel, numerous writers apologized for publishing their work, and since there is an absence of published work by the top-ranking aristocrats, I conclude that these apologies were not entirely affectations.

I now wish to relate all this to Veal’s specific criticism, which relies heavily on Kathman and Ross’s web page. Following is the section of Veal’s review relevant to the “stigma of print":

As in other anti-Stratfordian works, the “stigma of print” looms large in Miss Price’s picture of Elizabethan society. It is vital to her position, because it furnishes her sole explanation of why the real Shakespeare hid his authorship.

Elizabethan gentlemen wrote for others in their social circle with no thought of seeing their compositions in print. Custom prohibited the upper class gentleman from having any profession at all, writing included. To publish for public consumption was the business of the paid professional, not the gentleman. [218]

The “stigma” theory, devised in the 19th

Century to explain why so few Tudor aristocrats published their

works, has fallen out of favor for the simple reason that the

phenomenon that it sought to explain did not really exist. As Steven

May, the leading authority on Elizabethan courtier poets, has

demonstrated, those Elizabethan gentlemen who wrote at all (a small

minority) published quite a bit and were not disgraced thereby. Miss

Price ignores Professor May’s article in her book, though she claims

on her website to have read it (one of many instances in which she

deals with uncongenial analysis by averting her eyes). More

importantly, she makes no effort to examine the directly pertinent

question: Would an Elizabethan or Jacobean courtier who wrote plays

have had any strong motive to hide his authorship?

The case for a “stigma” is much weakened by the

fact that persons of high station did in fact write, or attempt to

write, for the theater. Sir Thomas Sackville, a cousin of the Queen

and later a baron and earl, co-authored Gorboduc, the first

noteworthy Elizabethan tragedy. It was printed under his name in

about 1570, evidently from a manuscript that he supplied. Two plays

by William Cavendish, earl of Newcastle, were presented at

Blackfriars, London’s most popular theater, in the early 1640’s.

Manuscripts, dated about 1600, survive of several dramas written by

Lord William Percy, a younger son of the earl of Northumberland, for

production by the Children of Paul’s. Noble authors whose works

never, so far as we know, reached the stage include Fulk Greville,

Lord Brooke, Mary Herbert, Countess of Pembroke (translator of a

blood-and-thunder French tragedy) and William Alexander, earl of

Stirling. Many of these pieces are conventionally labeled “closet

dramas", but, unlike Goethe’s Faust or Hardy’s The Dynasts,

they are not unactable epics or novels in dialogue.

Their form and structure differ not at all from popular

drama.

The “stigma of print" in Tudor England was not “devised” in the 19th century. According to May, it was Edward Arber who first wrote about the Tudor stigma of print, but then Arber is merely the first to have noticed the phenomenon. Far from having fallen out of fashion, the “stigma of print” remains an integral part of literary studies today.

The landmark study on this subject is J.W. Saunders’s 1951 essay “The Stigma of Print.” I also refer to his related article, “From Manuscript to Print,” and The Profession of English Letters. According to Saunders, the professional poet had “his eye on personal profit,” whereas the gentleman-amateur “attempted to keep poetry within private genteel circles and attached to appearance in print a formidable social stigma ("Stigma,” 155; “Manuscript,” 509). Saunders considered some of the mystifications that cloaked the well-born author in print, as well as some of the apologies and disclaimers that appeared when a work escaped into print: “Underlying many of the quotations … is a certain moral hesitation about the value of the imaginative literary arts, lyric poetry, drama, and so on, in which the Court excelled" (Profession, 60), so here Saunders touches on the frivolous nature of poetry, fiction, and drama.

Many Tudor gentlemen describe writing poetry as vain or foolish (e.g., Spenser’s “ydle rimes … The labor of lost time” (FQ, verse to Burghley); or Thomas Blenergasset’s “learned men, yet none which spende their tyme so vainely as in Poetrie” (Mirrour for Magistrates, cit. by Saunders, “Manuscript,” 512). According to Richard Helgerson, “as a plaything of youth, a pastime for idle hours, poetry might be allowed. … But as an end in itself, as the main activity of a man’s life, poetry had no place. … For the courtier, poetry could be only an avocation, never a vocation” ("Role,” 550). Pettie articulated this value in the preface cited above. It is this value system that underlies the aristocrat’s reluctance to be published. Helgerson also notes that while “the amateurs avoided print; the laureates sought it out.” He views Sidney as “that most nearly laureate of amateur poets” ("Laureate,” 201, 202), and of course, Sidney published none of his work during his lifetime.

Concerning characteristics common to both poetry and drama, Helgerson writes elsewhere:

If playwriting could so easily be made to occupy the place more commonly taken in an amateur career by verse-making, it was because both were supposed to be equally frivolous. Neither private verse nor public drama made the claim to literary greatness that distinguishes the laureate and his work. The courtly amateur claimed to write only for his own amusement and that of his friends; the professional, for money and the entertainment of the paying audience (“Laureate,” 206).

Helgerson has described two principal factors behind the stigma of publishing plays written for the public theaters; they were perceived as commercial and frivolous.

Among other 20th century authorities who have incorporated the concept of the stigma of print into their studies are:

These citations demonstrate that current scholarship accepts the stigma of print as a genuine phenomenon. However, the above cited authorities generally discuss the stigma in connection with poetry (but occasionally prose or drama). Let us now consider the works of aristocratic dramatists.

Veal claims that the aristocratic plays that were published in Tudor or Stuart England “are conventionally labeled ’closet dramas’ [but] … they are not unactable epics or novels in dialogue. Their form and structure differ not at all from popular drama.” Closet drama is not intended for performance, but it is not the actability of the plays that is at issue. It is the question of whether the aristocrat wrote plays to be performed on the public stage and published them with attribution. The purpose, the intended audience, and the venue are all of concern.

So, let us consider the published works that, according to Veal, demonstrate that there was no stigma of print. To arrive at a judgment, at least two factors need to be examined, (1) genre, and (2) circumstances of publication, including irregularities, signs of piracy or unauthorized publication, disclaimers, and so on.

Thomas Sackville : Gorboduc

Sackville (1536-1608) was son of Sir Richard Sackville, became Lord Buckhurst in 1567, and the earl of Dorset in 1604. Gorboduc was acted in 1562 at the Inner Temple, published in 1565, and reprinted in 1570 and 1590. At the time of publication, Sackville had no title, so its publication is irrelevant to the discussion.

Nevertheless, the 1565 edition was pirated (see Chambers, Stage 3:457 or Brooks, Printing, 30-31). According to the title page of the 1570 edition, the play was “written about nine years ago by the right honorable now Lord Buckhurst, and by T. Norton,” “was never intended by the authors thereof to be published,” and the original publisher obtained the play from “some yongmans hand that lacked a little money and much discretion.” There’s the disclaimer that demonstrates the stigma of print, in this case invoked perhaps since by 1570 one of its authors did have a title.

William Cavendish

Cavendish (1592-1676), the earl of Newcastle’s plays from the 1640s are too late to be relevant to the discussion.

Lord William Percy

Percy (1575-1648) was the third son of the 8th earl of Northumberland. The surviving plays in question are preserved in manuscripts that bear the initials “W.P., Esq.” According to Chambers (Stage, 3:464-65), Percy’s “authorship appears to be fixed by a correspondence between an epigram in the MS. to Charles Fitzgeffry with one Ad Gulielmum Percium in Fitzgeoffridi Affaniae (1601).” It is not know if they were ever performed at St. Paul’s, but it is certain that they were never printed during the author’s lifetime. The first play was not printed until 1824. Percy’s plays therefore cannot be cited to dispute the stigma of print.

Sir Fulke Greville : Mustapha

Greville (1554-1828) was knighted in 1603 and created Baron Brooke in 1621. Mustapha is a closet drama (May, Courtier, 167). According to M.E. Lamb, Mustapha is “overtly political in purpose and show[s] more concern in reforming the state than the stage” (“Myth,” 201). In the Dictionary of Literary Biography, Charles Larson writes:

Always the gentleman amateur, Greville never permitted any of his writings to be published while he was alive, and it was probably a considerable annoyance to him when an unauthorized printing of Mustapha appeared in 1609. His was not a drama written for the popular theater, and, indeed, he claimed in the Life of Sidney never to have had any intention of having his plays staged under any circumstances: “I have made these Tragedies, no Plaies for the Stage…. But he that will behold these Acts upon their true Stage, let him look on that Stage wherein himself is an Actor, even the state he lives in, and for every part he may perchance find a Player, and for every Line (it may be) an instance of life.” This is one of the most explicit statements extant on the theory of Elizabethan closet drama, and it is important to put a positive face on it: Greville most certainly does approve of drama as a literary form. Staged plays might be merely entertainment and thus the fit recipients of the attacks that the Puritans were waging against the theater at that moment, but the drama as a literary text engages the mind seriously and leads to important discoveries about the nature of life.

In particular, Greville “had difficulty writing ideological drama that is credible as dramatic literature. Of course, one should recall that he did not intend these plays for the stage" (Larson, DLB).

Mustapha was published without attribution. Even May describes the edition of Mustapha as “surreptitious" (Courtier, 325). Greville’s own surviving papers tell us explicitly about his ambivalence and reluctance to have any of his works published, even posthumously: “These pamphlets [i.e., his plays] which having slept out my own time, if they happen to be seene herafter, shall at their own peril rise upon the stage when I am not.”

Mary Sidney Herbert : Antonie

Mary (1561-1621), countess of Pembroke, was Sir Philip Sidney’s sister and a distinguished member of the nobility. According to the editors of her Works, the countess’s translation of Garnier’s Marc Antoine “emphasized political commentary” (Hannay, 38). It is classified as a “closet drama” (May, Courtier, 167), and “with its discussion of moral issues presented in set speeches rather than stage action, the genre would have been particularly suited to reading aloud by the assembled guests at an English country house like Wilson. Marc Antoine was successfully staged in France; however, there is no record that Pembroke’s translation was ever performed, even at Wilton” (Hannay, 41; see also Bergeron, “Women,” 70). Further, “the genre was also particularly suited for women who desired to write plays but would not be permitted to write for the public arena” (Hannay, 41).

Hannay et al. assume the countess authorized publication of her translation. May cautiously states that “the countess probably [emphasis added] authorized the publication of Antonie because it illustrated the precepts of dramatic tragedy formulated in [her brother’s] Defense … and asserted that a good ruler seeks to be loved rather than feared by his subjects” (May, Courtier, 167).

William Alexander : The Monarchicke Tragedies

William Alexander (1567-1640) was tutor to Prince Henry and came down to London from Scotland when James acceded the throne. He was raised to the rank of viscount in 1630 and to the earldom in 1633. His four historical tragedies on classical subjects, Darius, Alexander, Caesar, and Croesus, were first published at the beginning of James I’s reign and issued collectively as The Monarchicke Tragedies.

Alexander’s four tragedies are closet dramas. The only entry for him in the Dictionary of Literary Biography appears, significantly, in the volume of 17th century British Nondramatic [emphasis added] Poets. Beckett writes that “The plays in The Monarchicke Tragedies were never intended for the stage, as its dedication to King James makes clear. Each deals with the dangers of ambition in a monarch, and each is both didactic and sententious.” According to Lamb, “the grave political advice which fills his cumbersome Monarchicke Tragedies, dedicated to the new English king, strongly suggest a desire to establish himself as a wise counselor, not as a budding playwright” ("Myth,” 200). The circumstances of publication are straightforward, but at time of publication, he had no title. So again, this is irrelevant to the stigma of print as it affected the aristocracy.

Veal’s final criticism:

Of crucial importance too was the attitude of the monarch. Although plays were considered scarcely better than pornography in Puritan circles, those were not the sentiments that prevailed at the fons honoris. Elizabeth and James were theatrical enthusiasts. The Queen saw six to ten plays in an average season, the King twice as many. Virtually all of those works were drawn from the repertories that the leading professional companies presented in London. Contrary to what Miss Price imagines [264], there was, during the period of Shakespeare’s activity, no special category of “court plays” distinct from the commercial theater. There is, in short, no credible reason to think that a late Tudor aristocrat would have suffered at all from being known as the mind behind some of the most popular dramas of the day.

Veale must have missed the distinction between writing plays for academic, private, or royal venues, and being recognized as having written and published a commercial play. In addition, it was one thing to patronize a play at court; it was another to be seen as the author who wrote for public consumption.

CONCLUSION

Although writing closet drama was a respectable pastime, few aristocratic authors published their dramas. The countess of Pembroke “probably" authorized the publication of Antonie , but the circumstances remain unclear. Young master Percy’s plays were not published during his lifetime. Alexander wrote his plays, not for the stage, but to convince King James that he was fit to serve as a counselor to a monarch, and at the time that he did publish, he was newly arrived from Scotland and had no title. Gorboduc and Mustapha were printed without authorization, and at the time of publication, Sackville had no title.

In my book, I build the case that the works of Shakespeare were written by an unnamed nobleman, and that the stigma of print was a contributing factor to the appearance of another man’s name on the works. Having reconsidered the stigma of print in light of the criticism from Mssrs. Veal and Kathman, I have no reason to amend anything on this topic in my book. If the works of Shakespeare were written by an aristocrat, then that aristocrat had good reason to conceal his identity. In short, there is ample evidence to demonstrate the Tudor “stigma of print.” Today, literary critics continue to incorporate the phenomenon into their studies, and it remains a factor relevant to the Shakespeare authorship question.

POSTSCRIPT: According to Veal, “a bevy of gentlemen of rank wrote the prefatory verses to Spenser’s Faerie Queene, “but he has that back-to-front. Spenser addressed prefatory verses to a bevy of aristocrats, not they to him.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beckett, Robert D. “William Alexander” in the Dictionary of Literary Biography 121: Seventeenth-Century British Nondramatic Poets, ed. M. Thomas Hester. The Gale Group, 1992.

Bergeron, David M. “Women as Patrons of English Renaissance Drama.” In Readings in Renaissance Women’s Drama: Criticism, History, and Performance 1594-1998. Ed. S.P. Cerasano and Marion Wynne-Davies. London: Routledge, 1998.

Brooks, Douglas A. From Playhouse to Printing House. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Chambers, E.K. The Elizabethan Stage. 4 vols. 1961. Reprint, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1923.

Dutton, Richard. “The Birth of the Author.” In Elizabethan Theater: Essays in Honor of S. Schoenbaum, ed. R.B. Parker and S. P. Zitner, 71-92. Newark: University of Delaware Press. 1996.

Elizabethan Critical Essays. Ed. G. Gregory Smith. 2 vols. 1904. Reprint, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Google links to hlas.:

https://groups.google.com/g/humanities.lit.authors.shakespeare?hl=en%20

https://groups.google.com/g/humanities.lit.authors.shakespeare/search?q=%22Diana%20Price%22&hl=en%20

Hannay, Margarget P., Noel J. Kinnamon, and Michael G. Brennan, ed. The Collected Works of Mary Sidney Herbert, Countess of Pembroke. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Helgerson, Richard. “The Elizabethan Laureate: Self-Presentation and the Literary System.” ELH 46:2 (summer 1979): 193-220.

─────. “Role of the Poet.” Entry in Spenser Encyclopedia. Ed. A. C. Hamilton. University of Toronto Press, 1990.

Jones, Norman, and Paul Whitfield White. “ Gorboduc and Royal Marriage Politics.” English Literary Renaissance 26:1 (winter 1996): 3-16.

Kathman, David and Terry Ross. The Shakespeare Authorship Home Page : https://ShakespeareAuthorship.com/

Lacey, Robert. Sir Walter Raleigh. New York: Atheneum, 1974.

Lamb, Mary Ellen. “The Countess of Pembroke’s Patronage,” English Literary Renaissance 12 (spring 1982): 162-79.

─────. “The Myth of the Countess of Pembroke” in The Yearbook of English Studies 11 , London: Modern Humanities Research Assoc., London, 1981: 194-202.

Larson, Charles. “Sir Fulke Greville," Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 62: Elizabethan Dramatists. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Fredson Bowers, University of Virginia. The Gale Group, 1987.

Marotti, Arthur F. John Donne, Coterie Poet. The Univ. of Wisconsin Press, 1986.

─────. “Patronage, Poetry, and Print.” The Yearbook of English Studies: Politics, Patronage and Literature in England 1558-1658 , Special Number 21, (1991): 1-26.